Beautiful and unusual sky signatures

By Kay Turnbaugh

Cloud watching in Boulder County can be summed up in one word: spectacular. Even the U.S. Postal Service agrees; it featured two of our more unique clouds on a 2003 sheet of postage stamps called “Cloudscapes.”

One was a photo of cirrocumulus undulatus, taken in Coal Creek Canyon by weather observer Richard Keen. It shows dainty patches of small, puffy, ripply clouds arranged in patterns.

Carlye Calvin’s gorgeous photograph of lenticular clouds at sunset was shot at the top of Boulder Canyon, near Nederland’s Barker Dam, as the clouds turned a deep, fiery orange. The “Cloudscapes” sheet lacked a lenticular cloud, so the Postal Service contacted Calvin, a storm chaser and NCAR photographer who was known as a cloud expert. She wasn’t supposed to tell anyone until it was published. For three long years she kept her secret from everyone except her husband and her father, who died before he could see the published stamp.

NCAR held a cloud ceremony, and Calvin and Keen signed stamps, just like at a book signing. Even now, 14 years later, people still remember the glorious stamps and Boulder County’s contribution.

Since we are home to two of the nation’s best weather research agencies, we asked scientists at NCAR (National Center for Atmospheric Research) and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) what makes cloud watching in Boulder County so spectacular.

Margaret LeMone, author of The Stories Clouds Tell Us and Senior Scientist Emerita at NCAR, says the number one reason cloud watching is good in Boulder County is the fact that we can see the clouds. The air is dry and clear, and the cloud base is high. The second reason for spectacular clouds is our mountains. Clouds form as air on the ground rises and cools, and the dryer the air, the higher it has to rise before it condenses and forms the tiny liquid droplets that are visible as clouds. When the cloud base is higher it’s easier to see the clouds in all their fantastic permutations.

Here are a few suggestions of clouds to look for that are not often found elsewhere.

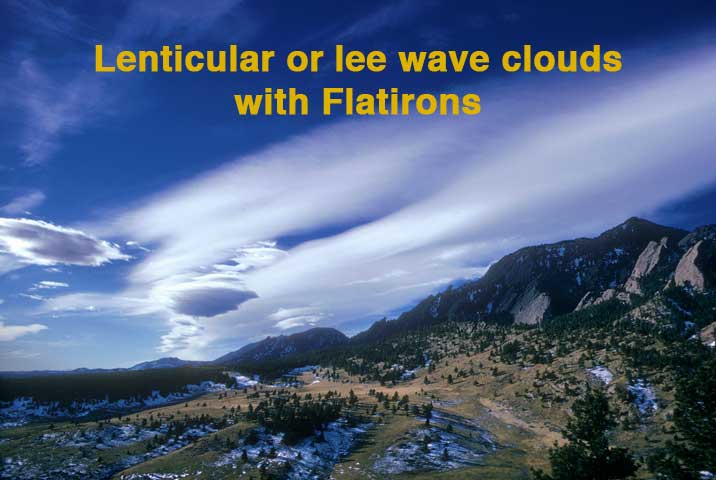

Lenticular clouds make flattened, lens-like shapes that also can look like saucers, which is why they have sometimes been mistaken for UFOs. They are associated with strong downslope winds, according to John McGinley, a retired NOAA meteorologist, and are “gorgeous in mornings and sunsets.” They form when air is forced up and over mountains where it condenses and stays in one place. They don’t move much, forming and reforming in the same place in single shapes or stacks. They can disappear quickly, although sometimes they stick around for hours.

Wave clouds are formed in much the same way. The wind blows perpendicular to the mountains and air is forced to rise on the windward side and descend the leeward slopes. As the air streams down the mountainside, it can start to oscillate in a series of waves, called mountain waves.

The lee wave clouds we see here are products of air moving over mountains and down the leeward side toward the east. When two layers of air in the clouds are traveling at different speeds, the waves curl into what is called Kelvin-Helmholz or shear-gravity waves, also known as billow or coat-hanger clouds. These clouds look much like little curly waves in the ocean.

Related to mountain wave clouds, long line clouds that form 10 to 20 miles from the mountains are unique to Boulder, says McGinley.

Rotor clouds are also particular to our area. These are low-level cumulus clouds associated with mountain wave clouds. They occur when air rises again, and under the cloud the wind reverses. They are indicative of severe turbulence and can be a hazard for aviation.

Other amazing clouds noted by LeMone and McGinley include iridescent clouds. Lenticulars are good for this. Although you can see iridescent clouds from the city, you also often see them when you’re flying in the mountains, or when you’re looking down from the top of a mountain. Iridescence is a diffraction phenomenon, and the colors we see are caused by the cloud’s small water droplets or small ice crystals individually scattering light. Which is why it’s usually visible along thinner edges of clouds or in semi-transparent clouds.

Other amazing clouds noted by LeMone and McGinley include iridescent clouds. Lenticulars are good for this. Although you can see iridescent clouds from the city, you also often see them when you’re flying in the mountains, or when you’re looking down from the top of a mountain. Iridescence is a diffraction phenomenon, and the colors we see are caused by the cloud’s small water droplets or small ice crystals individually scattering light. Which is why it’s usually visible along thinner edges of clouds or in semi-transparent clouds.

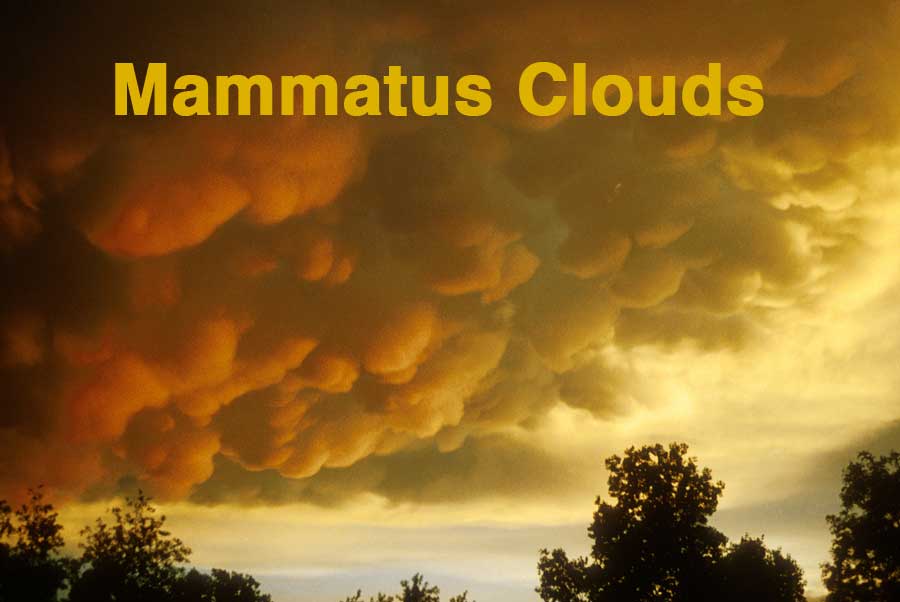

Clouds in the eastern part of the county are pretty spectacular too. Because of our clear skies and high cloud bases, thunderstorm clouds are amazing, says storm-chaser Calvin. They include the cumulonimbus anvil clouds and the mammatus clouds that form under the horn of the anvil. And, “Some of the coolest clouds are wedding cake clouds,” says Calvin. These are the layered clouds that form after a thunderstorm.

Clouds in the eastern part of the county are pretty spectacular too. Because of our clear skies and high cloud bases, thunderstorm clouds are amazing, says storm-chaser Calvin. They include the cumulonimbus anvil clouds and the mammatus clouds that form under the horn of the anvil. And, “Some of the coolest clouds are wedding cake clouds,” says Calvin. These are the layered clouds that form after a thunderstorm.

Among LeMone’s favorites are those lines that form in the wake of aircraft flying overhead. “The contrails around here are incredible,” she says. “The way they evolve varies, and it’s sometimes affected by the mountains.” Contrails, short for condensation trails, form behind jets in the very cold air around 30,000 to 40,000 feet. When the air is dry you can see only a short tail coming out of the back of the plane, as the plane gains altitude, its contrail becomes more visible. Contrails can reveal air motions and other processes just like other clouds, including wave clouds.

Read this story in Boulder Magazine.